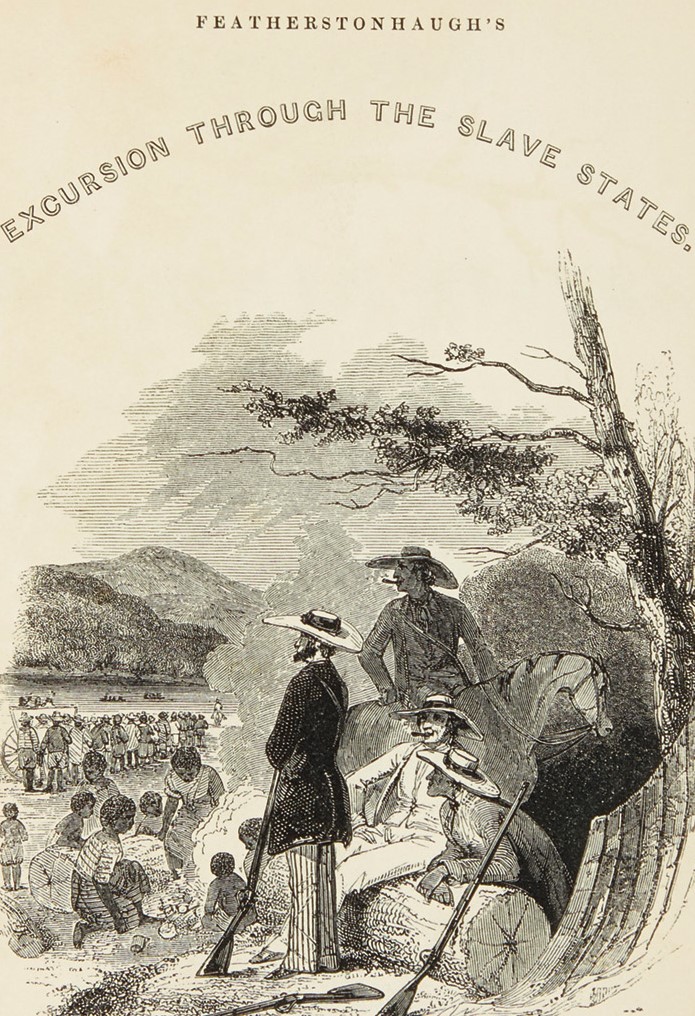

Arkansas has long had a reputation for bad roads. As American settlers moved toward the West in the early 1800s, transportation routes were not only rough and filled with curves, but also dusty in dry weather, and muddy on rainy days. Traveling across Arkansas Territory was difficult, and many travelers lamented the condition of the trails and roads of the day. One man who described his travels through Arkansas was George William Featherstonhaugh, who visited Arkansas in the early 1830s. His book about the journey, “Excursion Through the Slave States,” was published in 1844. Featherstonhaugh held generally negative views of Arkansas and offered not only a description of some of the road conditions he found as he traveled southwest from Little Rock, but also an explanation of how the poor roads evolved here in the first place:

“We again put our little wagon in motion, and directed our course towards the hot springs of Washita. For the first eight miles the road was very bad, full of rocks, stumps, and deep mud holes, and wound up one of those sandstone ridges that are so common in this country. We frequently came upon trees that had fallen across the road, and had lain there many years, exhibiting an indifference on the part of the settlers unknown in the more industrious northern states. When a tree falls on the narrow forest road, the first traveler that passes is obliged to make a circuitous track around it, and the rest follow him for the same reason. I have observed this peculiarity in Missouri and Arkansas. If a tree is blown down near to a settler’s house, and obstructs the road, he never cuts a log out of it to open a passage; it is not in his way, and travelers can do as they please, because nobody would prevent their cutting it. But travelers feeling no inclination to do what they think is not their business, never do it.

“The settler in these wild countries plants to live and not to take to market; if he is on horseback he cares little about it, if he is in a light wagon he can get round the tree in less time than it would take to stop and ‘work for others.’ Thus the old adage is verified, that ‘what is everybody’s business is nobody’s business;’ but what makes this unjustifiable indolence on the part of the settler—when the obstruction is near his house—sometimes is very absurd, is, that often when a track is established round the first fallen tree another obstruction shuts up this track, and so in a long period of time the established track gets removed into the woods, far out of sight of the settler’s house. If you ask him why he does not cut a log out of the first fallen tree, he will probably say that ‘it is not his business to wait upon travelers,’ and indeed the distances from house to house are sometimes so very great, that it would be unreasonable to require of any particular settler to remove all such obstructions.

“These circuitous tracks are known by the name of turn-outs, and if you are inquiring towards evening how many miles it is to the next settlement, you perhaps will be told, ‘16 miles and a heap of turn-outs.’ We once made a calculation that these turn-outs added at least five miles to our journey.”