As of 1700 no European or American Indian resident communities existed in the Ouachita Mountains, although the region hosted numerous transient populations until the time of permanent American settlement. French and Spanish hunters and traders penetrated the Arkansas wilderness in search of game and Indian trade, creating hunting camps at strategic places along rivers and streams. These camps led ephemeral existences; virtually no physical evidence of any of them remains today.

Ownership of the land that would later become Arkansas was claimed for France by LaSalle, who named the entire Mississippi valley region Louisiana, in honor of his king, Louis XIV. Following the French and Indian War, Spain came to own the area. Spain offered liberal land grants in an effort to attract settlers. However, in 1799 the Spanish enumerated only 368 people in the Arkansas area, illustrating the region’s sparse population. Spain returned ownership of Louisiana to France, and shortly thereafter, Napoleon Bonaparte faced a slave uprising in Haiti and war in Europe, so he sold the entire Louisiana area to the United States. With that “Louisiana Purchase,” Louisiana, a mass of land which included the huge Mississippi River basin drained by rivers flowing east to the river, became American property in 1803.

Arkansas was part of that Louisiana Territory. At the time, only two places could truly be called settlements in Arkansas. Both were near the Mississippi River, so neither sat in the Ouachita Mountains: hunters and traders still dominated the entire uplands region. In 1804, Lt. James Wilkinson reported the presence of thousands of buffalo, elk, deer, and other large game in the region, along with a few French hunters. Deer skins, furs, and bear fat remained important commodities, with New Orleans as the ultimate point of trade. Explorers William Dunbar and George Hunter, who traveled up the Ouachita River in 1804, mentioned a number of hunters in their reports. One note mentioned hunters’ use of a stream in the upper Ouachita River valley: This is a creek of considerable length and tolerably good navigation for small boats, the hunters ascend it to an extent of a hundred of their leagues in pursuing their game. They all agree that none of the springs which feed this creek are salt; it has obtained its name from many buffalo salt licks which have been discovered near to the creek.”

In fact, a number of place names in the area date back to early days and have French and Indian origins, including the previous example of the Saline “Creek.” For decades, the late Sam Dickinson of Prescott explored Arkansas place names and created a list containing the definitions and/or explanations behind some of the locations in this region. His research suggests the following name origins.

For example, according to Dickinson, one explanation of the word “Caddo” was that it was the English derivative of the name of an Indian tribe whom the French called “Les Caddauxy,” “Cadodaquio,” “Quadodaquious,” and “Cadodaquioux,” and whom the Spanish referred to as “Los Kadohadachos.” In the early 1800s the Caddo River was called by the French name, “Fourche des Cadaux,” meaning “Fork of the Caddos.”

The heritage of the name “DeGray” is a bit more uncertain. One potential theory emerges from the word “De gres” or sandstone, with the stream of this name so named for soft, easily cut, sandstone along its course. A plat from an 1819 survey calls it “Bayou Degraff,” however, and it may be that it comes from a personal name. The Dunbar and Hunter expedition near Bayou du Cypre met a party headed by an old German named Paltz who had been on the Ouachita forty years. Dickinson posits that perhaps Degraff was a German hunter, too.

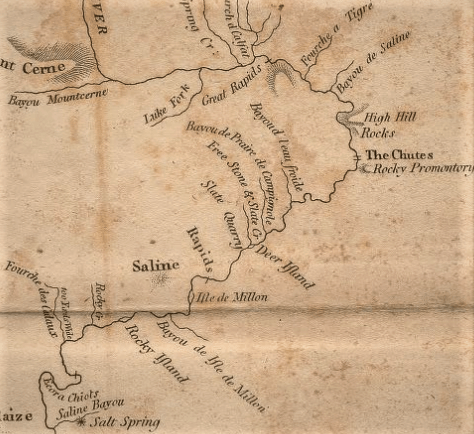

Then there is “Low Freight,” a creek likely first named by the French, “Leau froide.” An 1856 plat spells the name “Low Freight” although 1804 explorers Dunbar and Hunter called the creek “Bayaud l’eau Froide.” The location appears on a map drawn by Nicholas King shortly after the group returned from their journey.

Cachamassa, Cassamassa or Cassa Massa Bayou empties into the Ouachita River in Clark County. In 1908 a local historian wrote that it was the name of a Delaware Indian village. Delawares crossed this region, but according the Dickinson, evidence of a village is lacking. He believed that these spellings are most likely corruptions of Cache a Mason, “Mason’s Hiding Place.” The hunter who stored his things at the mouth of this stream could have belonged to the same French family at the Post of Ouachita for whom the bayou was named.

“De Roche,” a creek name, also became the name of a community. Explorer George Dr. Hunter referred to the stream as “Bayu des Roches,” translated to “Bayou of the Rocks.” He also mentioned the “Isle de roches,”or “Rocky Island,” on the Ouachita.

Watermelon Island, also known as Morrison’s Island, in the Ouachita River at the Midway community in Hot Spring County, was called “Isle de Millon,” or “Millon’s Island,” on an 1804 map. Hunter wrote it as “Mallon.” It is possible that the island was named for a person, but is more likely that “Mellon” and “Mallon” were misspellings of the French word, melon, which is the same in English.

Certainly, much research remains to be done to confirm and document the origins of these and other place names in the upper Ouachita River valley.