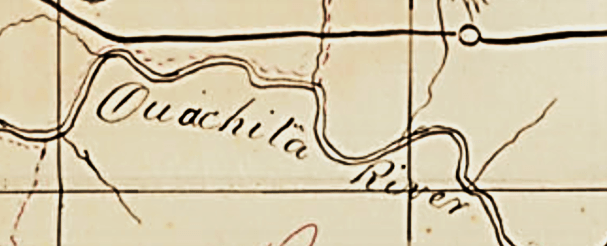

For centuries, the Ouachita River has carried the waters of its drainage area. The upper Ouachita existed as an untapped resource, and even a menace to some. The river’s change from a steep drop to a gradual descent resulted in a flooding problem for years. Prior to the construction of man-made dams on the upper portion of the river, water flowed downstream rapidly from the northwestern Garland County area when the river was full, but slowed down and spread out when it met slower-moving water below Camden in south Arkansas. These conditions resulted in extreme variation in streamflow, virtually eliminating the possibility of year-round travel on the river.

However, some river travel did take place on the upper Ouachita. Indians used the waterway for years, then after the arrival of Europeans in the area, French hunters and trappers frequently forded the river at Rockport. Because of the presence of “rocks” in the river, early American explorers William Dunbar and George Hunter struggled to navigate the rapids at Rockport during their expedition up the river soon after the Louisiana Purchase. During the 1830s, travelers along the Military Road (also called the Southwest Trail) often used Rockport’s boulders as a foundation on which to cross the river. But, with the advent of the steamboat, these same boulders prohibited vessels from regular river travel in the area. Because of the early prominence of these rocks in the river, the name “Rockport” is among the oldest continuously-existing town names in Arkansas.

It is believed that Clark County pioneer Jacob Barkman was the first to bring a steamboat up the river past what is now Arkadelphia. Barkman lived near what is now Caddo Valley at the confluence of the Caddo and Ouachita rivers, and used the river for trips to New Orleans. Barkman first traded with merchants to the south by means of pirogues, or large dugout canoes, but when his business began to grow, he needed larger and faster boats. So, he built a boat he called the “Dime.” The Dime was said to be a very nice boat, and it made regular trips up and down the river before it eventually sank. Local legend tells that the vessel got its name when a man who had seen much larger steamboats on the Mississippi River laughed and said, “Tain’t no bigger’n a dime!”

The Dime was small, but the largest boat known to come up to the upper portion of the Ouachita was the Will S. Hays. The Will S. Hays could carry 2,000 bales of cotton, and eventually sank on the river by being overloaded with that cargo. Many boats plied the Ouachita north from Camden prior to the Civil War, including the Alamo, C.M. Humphrey, Jo Jacques, Arkadelphia City, Francis Jones, Susie B., and Rock City. The Rock City once met with difficulties a few miles below Arkadelphia. The boat was apparently long and large for the river, and it lacked the power to successfully navigate the rapid and winding current of the upper Ouachita. Loaded with cotton and passengers, the boat failed to make a turn with the current and ended up broadside to an island, in danger of being broken to pieces. Several men drowned attempting to free the trapped vessel. It is believed the boat finally made it to safety.

Steamboats continued to travel the river even after the Civil War. In 1873, a man who lived between Arkadelphia and Rockport built a boat and took it down river. Because of construction on the new railroad bridge at Arkadelphia, he could go no further, so he sued the railroad for obstruction of navigation on the river, claiming damages in the amount of $10,000.00. Indeed, the railroad’s construction in the 1870s marked the beginning of a new era in transportation in Arkansas and the gradual demise of the steamboat.